Part Three

The Dropout

Part Three

The Dropout

Part Three The Dropout

No longer burdened with the toil of teachers, he sleeps in late in his own room, putters around the apartment most of the afternoon, and spends most evenings attending the plays and operas of Linz with his bosom companion, August Kubizek.2

As they stroll through town, Hitler, sporting a fashionable cane and the whisperings of a thin mustache, bends his compliant friend's ear with his opinions on everything and anything. Kubizek, known to Adolf as Gustl, is a gifted listener and absorbs his friend's oratorical tirades with awe and respect. The two companions walk the streets with growing familiarity, and climb the numerous hills about town for enthusiastic moonlight monologues expounding Hitler's visions.3

One of Hitlers recurring themes is the potential to turn Linz into a cultural center of German magnificence, with himself as chief designer. This will be another life-long passion for him, and he will design and re-design Linz, making numerous drawings and detailed layouts of an improved provincial capital. In early 1945, with the pounding of Russian artillery bombarding Berlin, Hitler will be found in his bunker hunched over a scale model of Linz.4

While large sections of Kubizekís memoirs should be treated with a degree of suspicion, there is much that can be relied upon.6 The spurious parts are ignored in this account, leaving only those incidents and anecdotes that either have second source confirmation, or that ring authentic in the context of over-all scholarship.7

For example, Franz Jetzinger was "deeply suspicious" concerning Kubizek's story of Adolf's long distance infatuation with Stefanie Jansten; but Jetzinger was surprised to discover that not only was Stefanie a real person, but that the time frame and other incidental details were borne out by his investigation. Jetzinger even interviewed Stefanie, who recalled receiving a strange letter from an unknown admirer declaring that he was about to enter the Vienna Academy of Art and would seek her out upon graduation. Having no recollection of the identity of the writer, she remembered the odd letter--and its fervent tone of adolescent romanticism--quite vividly.8

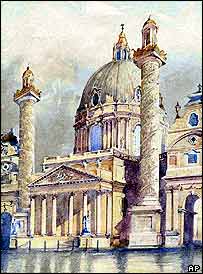

At the same time my interest in architecture, as such, increased steadily, and this development was accelerated after a two weeks' trip to Vienna which I took when not yet sixteen (Note: He is actually seventeen). The purpose of my trip was to study the picture gallery in the Court Museum, but I had eyes for scarcely anything but the Museum itself. From morning until late at night, I ran from one object of interest to another, but it was always the buildings which held my primary interest. For hours I could stand in front of the Opera, for hours I could gaze at the Parliament; the whole Ring Boulevard seemed to me like an enchantment out of The Thousand-and-One-Nights.

In sending you this postcard I must apologize for not writing to you for such a long time. I arrived safely, and I have been moving around industriously. Tomorrow I shall see Tristan at the Opera, and on the following day The Flying Dutchman, etc. Although I find everything very beautiful here, I am longing for Linz. Tonight, Stadt-Theatre. Greetings from your friend.

I cannot enthuse over the interior of the palace. While the exterior is hugely majestic, thus granting to it the severity of a monument of art, the interior, though commanding admiration, does not impress by its dignity. Only when the powerful sound waves flow through the theater and the whispering of the wind gives way to the terrible roar of those waves of sound, only then does one feel sublimity and forget the gold and velvet with which the interior is overloaded.

Sometime after his return from Vienna, Hitler and Kubizek visit St. Georgen on the River Gusen, the site of an ancient German battle. Hitler tells Kubizek that much could be learned from the "spirits" residing in the ancient soil, and in the mortar between the cracks of the ruined buildings.13

Mayor Mayrhofer, Adolf's guardian, joining the chorus of those encouraging Klara to compel Adolf to seek honest work, arranges for him to be apprenticed to a baker, but he refuses any such suggestion. The downstairs neighbors at the familyís Humboldtstrasse apartment are a postmaster and his wife. When the postmaster once suggested that Adolf should consider joining the postal service, he replied that he was intent on becoming a "great artist" someday. The postmaster's wife would later testify: "When it was pointed out that he lacked the necessary means and connections for this, he replied briefly: 'Makat and Rubens worked themselves up from poor circumstances.'"16

Of those last years we lived together with my mother I especially remember the cheerfulness of my brother and his extraordinary interest for history, geography, architecture, painting and music. At school he was nothing less than a show boy, came home with bad school reports and admonitions. At home every day he was sitting for hours on the beautiful Heitzmann grand piano, my mother had given him. This extraordinary interest for music, especially for Wagner and Liszt, remained with him for all his life. Particularly strong was even at that time already his interest for the theatre and especially for the opera. I can remember that he was visiting the opera house 13 times to hear Die Gotterdammerung. His Christmas present for his mother has always been a theatre ticket.

Dr. Eduard Bloch, known as the "doctor to the poor," was born in the tiny southern Bavarian village of Frauenburg. He set up practice in Linz at the turn of the century, after service in the Prussian Army as a military doctor. He has been the family physician since the Hitlers moved to the area, treating young Hitler many times for minor maladies.20

Their apartment consisted of three small rooms in the two-story house at No. 9 Bluetengasse, which is across the Danube from the main portion of Linz. Its windows gave an excellent view of the mountains. My predominant impression of the simple furnished apartment was its cleanliness. It glistened; not a speck of dust on the chairs or tables, not a stray fleck of mud on the scrubbed floor, not a smudge on the panes in the windows. Frau Hitler was a superb housekeeper. The Hitlers had only a few friends. One stood out above the others; the widow of the postmaster who lived in the same house. What kind of boy was Adolf Hitler? Many biographers have put him down as harsh-voiced, defiant, untidy; as a young ruffian who personified all that is unattractive. This simply is not true. As a youth he was quiet, well-mannered and neatly dressed. ....

He (Adolf) was tall, sallow, old for his age. He was neither robust nor sickly. Perhaps "frail looking" would best describe him. His eyes--inherited from his mother--were large, melancholy and thoughtful. To a very large extent this boy lived within himself. What dreams he dreamed, I do not know. Outwardly, his love for his mother was his most striking feature. While he was not a "mother's boy" in the usual sense, I have never witnessed a closer attachment. Some insist that this love verged on the pathological. As a former intimate of the family, I do not believe this is true.

In the last months of [my mother's] sickness, I had gone to Vienna to take the entrance examination for the Academy. I had set out with a pile of drawings, convinced that it would be child's play to pass the examination. At the Realschule I had been by far the best in my class at drawing, and since then my ability had developed amazingly; my own satisfaction caused me to take a joyful pride in hoping for the best.

Composition exercises in drawing. First day: expulsion from paradise, etc. Second day: episode from the deluge, etc. The following took the test with insufficient results, or were not admitted: Adolf Hitler, Braunau a. Inn, April 20, 1889, German Catholic. Father civil servant. 4 classes in Realschule. Few heads. Test drawing unsatisfactory.

Now I was in the fair city for the second time, waiting with burning impatience, but also with confident self-assurance, for the result of my entrance examination. I was so convinced that I would be successful that when I received my rejection, it struck me as a bolt from the blue. Yet that is what happened. When I presented myself to the rector, requesting an explanation for my non-acceptance at the Academy's school of painting, that gentleman assured me that the drawings I had submitted incontrovertibly showed my unfitness for painting, and that my ability obviously lay in the field of architecture; for me, he said, the Academy's school of painting was out of the question, the place for me was the School of Architecture.

It was incomprehensible to him that I had never attended an architectural school or received any other training in architecture.

Downcast, I left von Hansen's magnificent building on the Schillerplatz, for the first time in my young life at odds with myself. For what I had just heard about my abilities seemed like a lightning flash, suddenly revealing a conflict with which I had long been afflicted, although until then I had no clear conception of its why and wherefore. In a few days I myself knew that I should some day become an architect. To be sure, it was an incredibly hard road; for the studies I had neglected out of spite at the Realschule were sorely needed. One could not attend the Academy's architectural school without having attended the building school at the Technical, and the latter required high-school graduation. I had none of all this. The fulfillment of my artistic dream seemed physically impossible.

Hitler's assertion that he now realizes that he is destined for a career in architecture is unlikely. He will, after all, apply to the painting school again the next year. A thoroughly stunned and enraged young man lingers in Vienna for another month, bewildered as to how he will handle this entirely unexpected setback.36

As weeks and months passed after the operation Frau Hitler's strength began visibly to fail. At most she could be out of bed for an hour or two a day. During this period Adolf spent most of his time around the house, to which his mother had returned. He slept in the tiny bedroom adjoining that of his mother so that he could be summoned at any time during the night. During the day he hovered about the large bed in which she lay.

An illness such as that suffered by Frau Hitler, there is usually a great amount of pain. She bore her burden well; unflinching and uncomplaining. But it seemed to torture her son. An anguished grimace would come over him when he saw pain contract her face. There was little that could be done. An injection of morphine from time to time would give temporary relief; but nothing lasting. Yet Adolf seemed enormously grateful even for these short periods of release. I shall never forget Klara Hitler during those days. She was forty eight at the time (Note: She was really 46.);38 tall, slender and rather handsome, yet wasted by disease. She was soft-spoken, patient; more concerned about what would happen to her family than she was about her approaching death. She made no secret of these worries; or about the fact that most of her thoughts were for her son. "Adolf is still so young." she said repeatedly.

During this time my mother was severely ill we were most unhappy. Assisting me, my brother Adolf spoiled my mother during this time of her life with overflowing tenderness. He was indefatigable in his care for her, wanted to comply with any desire she could possible have and did all to demonstrate his great love for her. Her last desire was accomplished; she was buried beside the father. We accompanied her on her last way from Linz to Leonding, where she was buried...

December 20, 1907: Dr. Bloch visits a weak and failing Klara Hitler, determining that the end could come at any time. August Kubizek visits, finding her unable to speak above a whisper. "Go on being a good friend to my son," she tells him. "He has no one else.42He would watch her every movement, so that he might anticipate her slightest need. His eyes, which usually gazed mournfully into the distance, would light up whenever she was relieved of her pain. .... In all my career, I have never seen anyone so prostate with grief as Adolf Hitler.43

December 21, 1907: Klara Hitler passes away quietly in her room. Adolf sits next to her and solemnly sketches her portrait in death.44

It was a difficult blow. I had honored my father, but my mother I had loved. Her death put a sudden end to all my high-flown plans. Poverty and hard reality compelled me to make a quick decision. I was faced with the problem of somehow making my own living.

Hitler would have us believe that (1) he was flat broke and without means, and (2) that he immediately set off to make his way in the world. Neither contains much fact.46 Once Klara's estate is settled, the medical bills and funeral costs paid, Paula (being raised by the Raubals), and Adolf, will walk away with 1,000 Kronen apiece (some of it doled out subsequently by Mayor Mayrhofer, Adolf's guardian): about equal to the yearly salary of an Austrian schoolteacher. Added to the remaining funds from Aunt Johanna's loan for Adolf's schooling in Vienna, he will have enough to enable him to live for at least a year before being forced to find a way to acquire income.

There is no doubt whatsoever that Hitler is aware that Dr. Bloch is a Jew. Bloch will later testify that he at no time detected the slightest trace of anti-Semitism from Adolf or any of the Hitlers. When Jewish doctors are forbidden to practice in Hitler's Germany, Bloch will be excluded from the most severe restrictions. Years later, Hitler will personally arrange for the Jewish doctor to leave the country unmolested, though without his savings. He will die in poverty in New York City in 1945.48

Heinrich Himmler later complained, "...they all come along, the eighty million good Germans, and each one has his decent Jew. Of course the others are swine, but this one is a first-class Jew," in other words, a Jew worth saving. Even Adolf Hitler, apparently.49

During this time, Hitler pressures and cajoles Gustl into quitting the family's furniture business, into joining him in Vienna, and entering the Vienna Academy of Music.50

During his stay in Vienna, he had made detailed enquiries about the study of music, and now he gave me exact information on the subject, telling me, in his tempting way, how much he had enjoyed attending operas and concerts. My mother's imagination was also fired by these vivid descriptions, and so a decision became more and more imperative. It was, however, essential that Adolf himself should convince my father. A difficult enterprise! ...

He was quite fond of Adolf but, after all, he only saw in him a young man who had failed at school and thought too highly of himself to learn a trade. My father had tolerated our friendship, but actually would have preferred a sounder companion for me. Adolf was, therefore, in a decidedly unfavorable position. It is astonishing that he nevertheless managed to win over my father to our plan in so comparatively short a time. Ö. At the beginning of February, Adolf returned to Vienna. His address remained the same, he told me when he left, as he had continued to pay his rent to Mrs. Zakreys, and I should write to him in good time announcing my arrival.

With a suitcase full of clothes and underwear in my hand, and an indomitable will in my heart, I set out for Vienna. I, too, hoped to wrest from fate what my father had accomplished fifty years before; I, too, hoped to become something, but in no case a civil servant.

End of Part Three.

Written by Walther Johann von Löpp Copyright © 2011-2013 All Rights Reserved Edited by Levi Bookin — Copy Editor European History and Jewish Studies

Disclaimer:The Propagander!™ includes diverse and controversial materials--such as excerpts from the writings of racists and anti-Semites--so that its readers can learn the nature and extent of hate and anti-Semitic discourse. It is our sincere belief that only the informed citizen can prevail over the ignorance of Racialist "thought." Far from approving these writings, The Propagander!™ condemns racism in all of its forms and manifestations.

Fair Use Notice: This site--The Propagander!™--may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of historical, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, environmental, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a "fair use" of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.